Resuscitation: A Review of the Methods, Benefits, Risks, and Clinical Utility of Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA) in Civilian Trauma

Introduction

Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA) is a rapidly employed, minimally invasive procedure available for the treatment of life-threatening, non-compressible hemorrhage of the trunk and junctional regions (axilla and groin). Unlike hemorrhage from an injured extremity, which may be staunched with compression and tourniquet use and therefore generally has good outcomes [1], junctional hemorrhage can only be controlled by surgical and endovascular techniques. Due to delays in hemorrhage control, torso injuries account for roughly 90% of exsanguination deaths [2].

Several temporizing measures are available prior to definitive hemorrhage control. The emergent resuscitative thoracotomy (ERT) has been used since at least 1906 for the management of profound hemorrhagic shock due to penetrating thoracic trauma [3]. This procedure involves an incision in the anterior chest extending to the pleural space, and as appropriate clamping of the source of bleeding, pericardiotomy, cross-clamping of the descending aorta, and cardiac massage [3]. Understandably, this extremely invasive procedure is appropriate only for patients in extremis with loss of vital signs, is associated with numerous complications, and typically has poor outcomes [4,5].

REBOA offers a less invasive and potentially more effective alternative to ERT with aortic cross-clamping. This technique uses the percutaneous insertion of a balloon that inflates in the aorta and has been employed in traumas since the Korean War.[6] REBOA has recently gained popularity, although it is still not widely used and has experience in civilian populations is limited.

Method

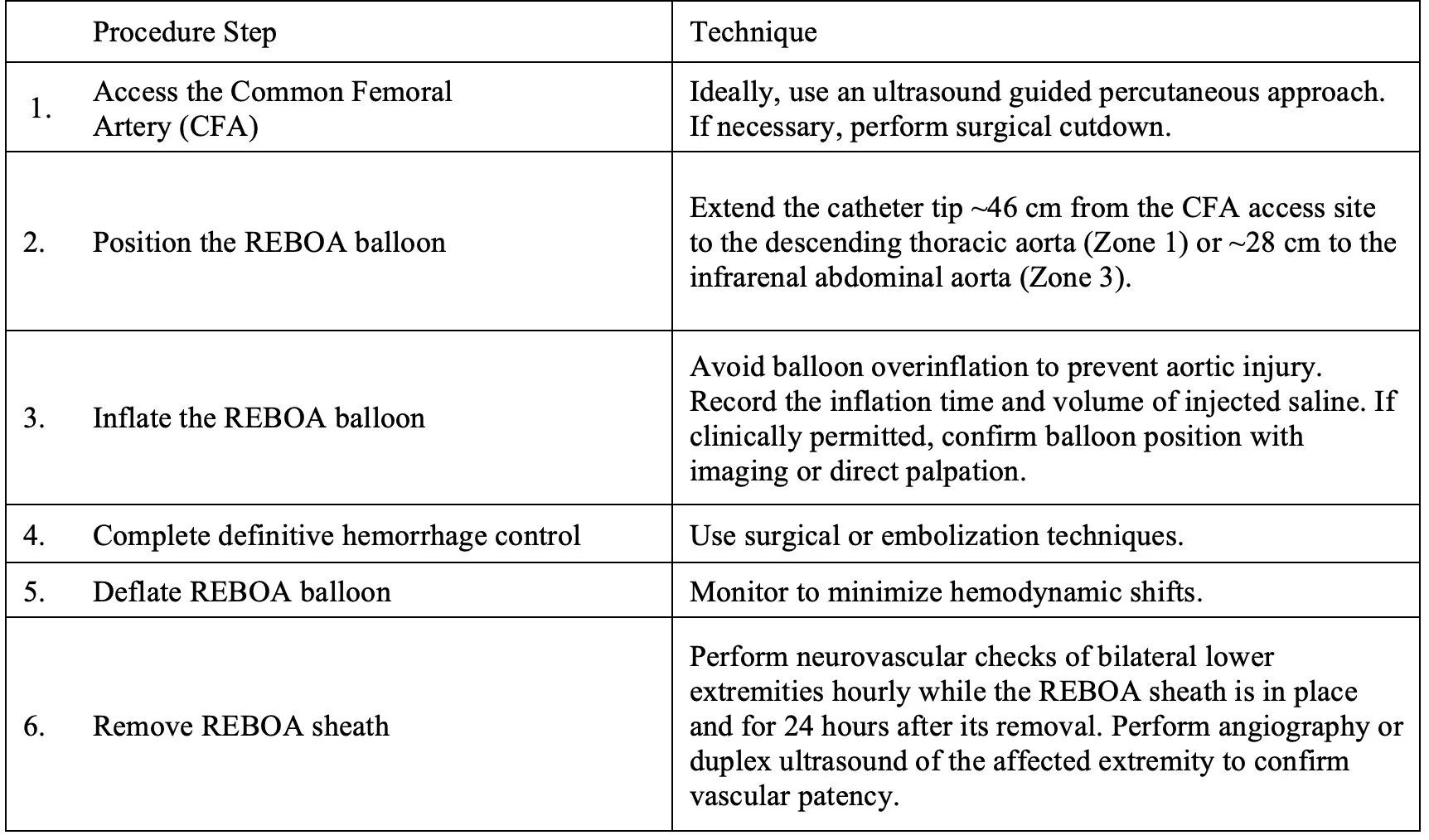

The steps for performing REBOA are summarized below in Table 1. Briefly, a catheter is advanced to the aorta through access via the common femoral artery (CFA). The balloon may be inflated to partially or completely occlude either the descending thoracic aorta in Zone 1 or the infrarenal abdominal aorta in Zone 3, depending on the suspected location of the hemorrhage (Figure 1) [7]. Occlusion in Zone 1 reduces bleeding within the abdomen, pelvis, and lower extremities, whereas occlusion in Zone 3 preserves perfusion to the abdomen while reducing bleeding from the pelvis and lower extremities [5].

Table 1. Steps for the deployment of REBOA

Figure 1. Anatomical positioning of REBOA in either Zone 1 or Zone 3 of the aorta

The aortic occlusion time should be monitored and limited, proceeding to definitive hemorrhage control as rapidly as possible, ideally within 15 minutes of REBOA placement in Zone 1 or within 30 minutes of placement in Zone 3 [7]. Although there is insufficient evidence for its efficacy, some centers have protocolized partial occlusion or intermittent occlusion of the aorta with REBOA to minimize complications [8,9].

Potential Benefits of REBOA

REBOA is used in the management of life-threatening hemorrhage from non-compressible sites. It blocks blood loss inferiorly, improving cardiac index and thus maintaining cerebral and myocardial perfusion [2,10]. Some studies suggest that REBOA improves survival in patients with hemorrhagic shock not requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation when compared to ERT [11]. REBOA has also been proposed for use in hypotensive patients at risk for hemorrhagic shock but who do not meet criteria for ERT [9].

Potential Risks of REBOA

There are significant ischemic risks distal to the REBOA balloon due to the temporary occlusion of the aorta. These effects may result in local ischemia, reperfusion injury causing kidney injury or multisystem organ failure, and systemic metabolic acidosis [12,13]. Complications are possible at the CFA access site, including hematoma, dissection, pseudoaneurysm, thromboembolism, and limb ischemia resulting in amputation [13]. Aortic injury can also occur during catheterization and balloon inflation, causing intimal tears, dissections, and ruptures that may be fatal [13].

Current & Future Directions

While the idea of temporary aortic occlusion prior to definitive hemorrhage control is conceptually attractive and is well supported by large animal studies [14], the current evidence for REBOA in humans is inadequate and inconsistent [7]. Most reports of REBOA use come from case series and cohort studies and even the three most recent reviews and meta-analyses have arrived at divergent results [2,5,15]. The only randomized clinical trial of REBOA use, published this year, was a small study performed in United Kingdom emergency departments that found that REBOA with standard of care was associated with an increased frequency of mortality due to hemorrhage when compared to standard of care alone [16]. However, this study population was composed predominantly of blunt trauma victims and had a relatively long period time from injury to balloon deployment. These factors may have limited the generalizability of the study results. Despite equipoise in the data, a joint statement by the American College of Surgeons and the American College of Emergency Physicians recommends REBOA for management of hemorrhagic shock resulting from traumatic vascular injury below the diaphragm that is not responsive to resuscitation [7]. Additionally, military guidelines recommend REBOA in certain cases of blunt and penetrating traumatic cardiac arrest [10].

Due to a relatively recent resurgence in interest, insufficient data supporting its clinical use, and resource and training limitations, most trauma centers in the U.S. do not perform REBOA. A minority of large-volume institutions have protocolized REBOA for the management of non-compressible torso and junctional hemorrhage, yet there are no standardized society guidelines regarding its indications or methods to minimize its complications.

Establishing guidelines for REBOA is difficult due to inherent problems in studying its clinical use. Comparing REBOA with ERT or other hemorrhage control measures typically involves selection bias and confounding, as patients receiving ERT are already in cardiac arrest and will therefore reliably have worse outcomes, whereas patients receiving REBOA have already failed resuscitation, thus reliably favoring other hemorrhage control measures [7]. Due to resource constraints, most studies do not examine outcomes after the initial resuscitation and thus fail to measure delayed complications or mortality. Future research should focus on comparing REBOA with ERT or standard of care using randomized controlled trials and should include patients presenting with diverse etiologies of exsanguinating hemorrhage.

AUTHORED BY: MATTHEW MCCABE, MS4 CWRU SOM

FACULTY EDITING BY: COLIN MCCLOSKEY, MD

References

Kauvar, D.S., Lefering, R., Wade, C.E. (2006). Impact of Hemorrhage on Trauma Outcome: An Overview of Epidemiology, Clinical Presentations, and Therapeutic Considerations. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 60(6), S3-S11. http://doi.org/10.1097/01.ta.0000199961.02677.19

Borger van der Burg, B.L.S., van Dongen, T.T.C.F, Morrison, J.J., Hedeman Joosten, P.P.A, DuBose, J.J., Horer, T.M., & Hoencamp, R. (2018). A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of the use of Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta in the Management of Major Exsanguination. European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery, 44, 535-550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-018-0959-y

Pust, G.D., & Namias, N. (2016). Resuscitative thoracotomy. International Journal of Surgery, 33, 202–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.04.006

Morrison, J.J. & Rasmussen, T.E. (2012). Noncompressible Torso Hemorrhage: A Review with Contemporary Definitions and Management Strategies. Surgical Clinics of North America, 92, 843-858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suc.2012.05.002

Castellini, G., Gianola, S., Biffi, A., et al. (2021). Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA) in Patients with Major Trauma and Uncontrolled Haemorrhagic Shock: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. World Journal of Emergency Surgery, 16(41). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-021-00386-9

Hughes, C. (1954). Use of an Intra-aortic Balloon Catheter Tamponade for Controlling Intra-abdominal Hemorrhage in Man. Surgery, 36(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.5555/uri:pii:0039606054902664

Bulger, E.M., Perina, D.G., Qasim, Z., et al. (2019). Clinical use of Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA) in Civilian Trauma Systems in the USA, 2019: A Joint Statement From the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma, the American College of Emergency Physicians, the National Association of Emergency Medical Services Physicians and the National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians. Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open, 4, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1136/tsaco-2019-000376

Dubose, J.J. (2017). How I do it: Partial Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Ccclusion of the Aorta (P-REBOA). Journal of Trauma & Acute Care Surgery, 83,197–199. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000001462.

Russo, R.M., White, J.M., Baer, D.G. (2021). Partial Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta: A Systematic Review of the Preclinical and Clinical Literature. Journal of Surgical Research, 262, 101-114. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2020.12.054

Glaser, J., Stigall, K., Cannon, J., et al. (2020). Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA) for Hemorrhagic Shock. Joint Trauma System Clinical Practice Guideline. Accessed: http://prytimemedical.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/REBOA_-CPG_FINAL.pdf

Brenner, M., Inaba, K., Aiolfi, A., et al. (2018). Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta and Resuscitative Thoracotomy in Select Patients with Hemorrhagic Shock: Early Results from the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma's Aortic Occlusion in Resuscitation for Trauma and Acute Care Surgery Registry. Journal of the American College of Surgery, 226(5), 730-740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.01.044

Joseph, B., Zeeshan, M., Sakran, J.V., et al. (2019). Nationwide Analysis of Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta in Civilian Trauma. JAMA Surgery, 154(6), 500-508. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0096

Manzano-Nunez, R., Claudia, O., Herrera-Escobar, J., et al. (2018). A Meta-analysis of the Incidence of Complications Associated with Groin Access After the use of Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta in Trauma Patients. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 85(3), 626-634. https//doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000001978

White, J.M., Cannon, J.W., Stannard, A., Markov, N.P., Spencer, J.P., & Rasmussen, T.E. (2011). Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta is Superior to Resuscitative Thoracotomy with Aortic Clamping in a Porcine Model of Hemorrhagic Shock. Surgery, 150(3), 400-409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2011.06.010

Bekdache, O., Paradis, T., Shen, Y.B.H., et al. (2019). Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA): A Scoping Review Protocol Concerning Indications, Advantages and Challenges of Implementation in Traumatic Non-compressible Torso Hemorrhage. BMJ Open, 9(2), e027572. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027572

Jansen, J.O., Hudson, J., Cochran, C., et al. (2023). Emergency Department Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta in Trauma Patients with Exsanguinating Hemorrhage: The UK-REBOA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA, 330(19), 1862-1871. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.20850