Intern Ultrasound of the Month: A Left Atrial Aneurysm & Review of the Basics

The Case

45-year-old female with a history of anemia, DVT (not on anticoagulation), abnormal uterine bleeding secondary to fibroids presented to the Emergency Department for lightheadedness and a drop in hemoglobin on outpatient labs. She reported heavy bleeding for a few months, for which she was receiving hormonal injections. She also mentioned new lightheadedness, worse with standing, but denied any weakness, chest pain, shortness of breath, abdominal pain, dysuria, hematuria, or any blood in the stool. No history of recent sexually transmitted infections or any vaginal discharge aside from vaginal bleeding.

Vitals on arrival were: 37.3 C, HR 109, RR 18, SpO2 100% on RA, BP 145/85 and remained stable. On physical exam, a holosystolic 3/6 murmur was noted, but otherwise, her examination was unremarkable. She was walking around the department without becoming symptomatic. Work up showed a negative pregnancy test and iron-deficiency anemia. EKG showed no significant findings aside from left atrial enlargement.

While her symptoms were thought to be most likely anemia-induced, a cardiac point-of-care ultrasound was performed to evaluate for additional etiologies of her lightheadedness.

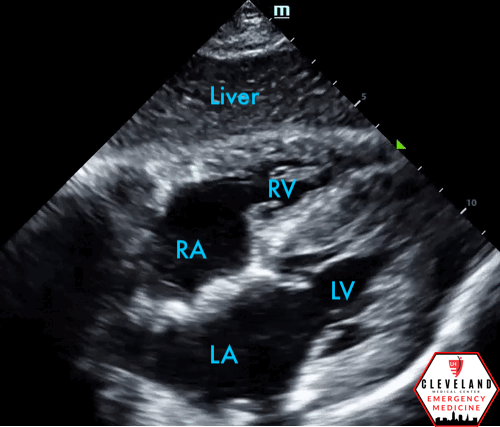

POCUS Findings

LV function is preserved, there’s no pericardial effusion or signs of right heart strain. There is, however, a large left atrial aneurysm, best seen in the apical 4 chamber view and especially in the subxiphoid view. When color doppler was applied, there was no significant mitral (or other valvular) regurgitation or abnormalities. No prior images to compare.

Case Continued

On further questioning, the left atrial aneurysm was known to the patient. She had a family history of this and she had been diagnosed in her late 30s but had not proceeded with surgery. She received a blood transfusion for her anemia and was admitted to the OB/Gyn service for further management of her uterine bleeding. In addition to blood products, she received iron supplementation and medroxyprogesterone and did well. She was discharged with outpatient follow up.

Left Atrial Aneurysm

Background

Left atrial aneurysm (LAA) is a rare cardiac structural anomaly that is most commonly congenital and diagnosed after the 2nd-3rd decade of life, though it can also be acquired [1-2]. LAAs are most commonly found in the left atrial appendage but can also be seen in the atrial wall [2]. Prior studies suggest that left atrial wall aneurysms are due to atrial septal defects or areas of weakness in the left atrial wall. Valvular abnormalities are usually not seen with congenital aneurysms [3,4].

Occasionally, LAAs are acquired due to multiple reasons. Elevated left atrial pressures as seen in mitral stenosis or mitral regurgitation can cause ballooning of the left atrium. Inflammatory or degenerative processes such as rheumatic heart disease, tuberculosis, and syphilitic myocarditis may also cause weakening in the atrial wall. One case study involving a middle aged man presenting with chronic chest discomfort showed fatty infiltration of the left atrial appendage resulting in a subsequent aneurysm. Nonetheless, acquired left atrial abnormalities are usually associated with valvular abnormalities, regardless of initial cause [2,3,5,6].

Clinical Presentation

Left atrial aneurysms may present symptomatically or asymptomatically. Congenital LAAs may present symptomatically in infants and can cause heart failure, respiratory distress, or even cardiac arrest, due to the displacement of mediastinum and subsequent airway obstruction [1-2]..

Symptomatic adults with LAA typically present with palpitations, dyspnea on exertion, chest pain, myocardial ischemia, and tachyarrhythmias, including supraventricular tachycardia or atrial fibrillation/flutter. On physical exam, a holosystolic murmur suggestive of mitral regurgitation can occur [2,3,6]. Many LAAs are asymptomatic and are found incidentally with an enlarged cardiac silhouette or mediastinal mass on chest x-ray or CT [2].

Diagnosis

Cardiac echocardiography is commonly used in the diagnosis of left atrial aneurysm. Transthoracic echocardiography can be a great non-invasive modality for visualizing left atrial wall aneurysms. However, transesophageal echocardiography is the most accurate imaging modality as it allows for more comprehensive visualization of the atrium and appendage, though this is invasive [1,2,6]. MRI is another preferred option as it allows for evaluation of surrounding structures, is non-invasive, and avoids radiation [2].

Management and Potential Complications

Even in asymptomatic patients, surgical excision early on in the disease is recommended to prevent complications of an enlarging LAA, as these can be life-threatening. Prognosis after surgical resection is typically favorable [6].

Delayed surgical excision can result in severe complications. LAA may cause tachyarrhythmias or cardiac tamponade due to limited diastolic expansion of the LV. It may also lead to pulmonary and systemic embolization, especially if the aneurysm is located in the appendage, heart failure, and potentially rupture [1, 2].

Despite the benefit of surgery, there are cases of LAA being managed conservatively. This has often in patients whose left atrial aneurysm is located in the appendage and found incidentally without symptoms. Those that are high risk with LAA should be treated with anticoagulation to prevent systemic embolization. Due to the limited number of cases, there is no agreement as to how and when left atrial aneurysms should be monitored [5].

Back to the Basics: How to Perform a Focused Cardiac Ultrasound, A Review

Focused cardiac ultrasound or cardiac point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is a non-invasive tool that can help quickly evaluate numerous presentations in the emergency department, including chest pain, shortness of breath, lightheadedness, hypotension, or any concerns for impaired cardiac contractility or outflow. It can also help differentiate shock states and guide resuscitation of critically ill patients. While it doesn’t replace comprehensive echo, POCUS has great diagnostic utility. It can answer focused clinical questions and provide invaluable information at the bedside that can alter management in real time [7-8].

Ideally, cardiac ultrasound should be performed using a phased array probe, which is a low-frequency probe with a small footprint to maximize detail. If possible, patients should be positioned roughly 30 degrees upright to bring the heart closer to the chest wall and allow for optimal cardiac visualization. The probe indicator should be directed to the operators left, which should coincide with the indicator on the left side of the ultrasound screen. It can also be helpful to think about the face of a clock when thinking about the direction of the indicator for each view. Findings should be confirmed in at least 2 views [7, 8].

Probe, Positioning, Mode, & Orientation

Ideally, cardiac ultrasound should be performed using a phased array probe, a low-frequency probe with a small footprint, which is useful for imaging between ribs. Patients should be positioned supine with head of bed approximately 30 degrees upright or, if possible, in a lateral decubitus position to bring the heart closer to the chest wall to allow for optimal cardiac visualization. Additionally, selecting a “cardiac” preset or mode on your machine will further optimize visualization of cardiac structures in motion [7-9].

Probe orientation for cardiac assessments is unique in that there are different conventions, the traditional cardiology convention and the more recently developed emergency medicine convention. The cardiology convention, (which is what we have adopted at our institution and will refer to here), places the indicator on the RIGHT side of the ultrasound screen. While this is in contrast to all other ultrasound applications, it is more widely accepted by cardiologists and other specialists outside of emergency medicine. Both conventions are accepted in clinical practice and can produce the same images; it just requires rotation of the probe to yield the same results. It can be helpful to think about the face of a clock when thinking about the direction of the indicator for each view. More than one view should be obtained. [7-9].

Probe placement/orientation using cardiac preset.

As a general rule of thumb: for cardiac settings, the indicator on the screen is on the right and the probe indicator points toward patient LEFT (the only exception is parasternal long axis). Conversely, for abdominal settings, the screen indicator is on the left and the probe indicator faces patient right.

Focused Clinical Questions/Indications

Is there cardiac activity?

What is the global LV function/contractility? — qualitative (normal, decreased, severely decreased, hyperdynamic)

Is a pericardial effusion present?

Is the RV grossly enlarged?

The Views

The following are the four standard views for cardiac POCUS that can each provide useful information and help answer the focused clinical questions.

Parasternal Long Axis

Parasternal Short Axis

Apical Four Chamber

Subxiphoid

The Cardiac Views.

Parasternal Long Axis (PSLA)

Location: left 3rd or 4th intercostal space, just lateral to the sternal border (note that this can vary from one patient to the next, so you may need to slide the probe down a rib space and/or slightly laterally to acquire an adequate window)

Indicator/probe position: toward patient’s right shoulder (~10 o’clock)*, keeping the probe relatively perpendicular to the chest

View: an adequate view will include good visualization of the left atrium, mitral valve, aortic valve/outflow tract. The heart should have a horizontal orientation with the left ventricle in the far field and the right ventricular outflow tract in the near field.

Assessment: assess for global LV function/contractility, presence of pericardial (versus pleural) effusion, RV size and aortic root dilation (RV, aortic outflow tract, and LA diameter should be roughly 1:1:1)

Tips: Slow, deliberate probe movements can lead to better visualization of the required structures; sometimes just moving off of a rib can make a big different. Also, be sure to have enough depth to visualize the descending aorta as this can help differentiate pericardial (fluid tracks anteriorly) from pleural effusion (fluid tracks posteriorly).

Parasternal Short Axis (PSSA)

Location: ~90 degree rotation from PSLA view, same intercostal space; the probe shouldn’t move much otherwise

Indicator/probe position: towards patient’s left shoulder (1-2 o’clock)*; probe itself should be relatively perpendicular to the chest wall

View: cross section of the left and right ventricles. Normally, the LV is circular appearing, while the RV is more crescent-shaped. While a short axis view can be obtained at multiple levels of the heart, the primary assessment for focused echo is at the level of the papillary muscles, as this is the best way to assess overall LV function.

Assessment: Assess LV function/contractility, RV enlargement and signs of strain (i.e. septal flattening, or “D sign”). This is also a great view for identifying regional wall motion abnormalities.

Tips: Be sure to visualize the papillary muscles, which should be relatively symmetric. An off-axis or oblique view can lead to misinterpretation.

Apical 4 Chamber

Location: at the apex of heart, near the PMI, just inferior to the left breast/nipple or more laterally

Indicator/probe position: probe marker should point towards the patient’s left (~2-3 o’clock)* with the probe directed cephalad upward and slightly medially, toward the heart (more flattened rather than perpendicular)

View: visualize all four chambers, with apex in the near field and the atria in the far field, and the right-sided chambers on screen-left and left-sided chambers on screen-right. The septum should be vertically aligned.

Assessment: a good view to compare RV and LV size, as well as assess overall cardiac function and pericardial effusion.

Tips: left lateral decubitus can improve visualization. Try to avoid an oblique or foreshortened view (which can happen when the probe is placed too cephalad or medial rather than at the true apex of the heart) — this often makes the RV appear relatively larger than it actually is and can lead to misinterpretation

Subxiphoid

Location: inferior to the xiphoid process

Indicator/probe position: indicator toward patient left (~3 o’clock position), pressing downward, parallel to the patient's skin. Direct the probe toward the heart/patient’s left shoulder

View: visualization of all four chambers with the RV adjacent to the liver, which is in the near field.

Assessment: this view is particularly good for assessing for pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade. From this view you can rotate the probe 90 degrees to visualize the IVC entering the right atrium for a rough assessment of volume status.

Tips: use the liver as an acoustic window by sliding the probe slightly toward the patient’s right (while still pointing the probe toward the patient’s left shoulder); have enough depth to visualize the whole heart. If you’re having trouble viewing the heart, have the patient take a deep breath and hold it (just make sure you hold your breath with them!)

This is often a preferred view for patients with COPD.

*These follow the cardiology convention using “cardiac” preset on the machine. If you use the abdominal setting or follow EM convention (with the indicator on screen LEFT, just rotate your probe 180 degrees from what’s noted above and you should get the same image!

Pearls & Pitfalls

If one cardiac view isn’t the best, try another view. Different views can give you similar information about the same pathology.

Always obtain more than one view! The more views, the better the assessment!

Patients will have slightly different anatomy and learning how the heart is positioned relative to the other anatomical landmarks and knowing how to troubleshoot is very helpful.

Subtle probe movements (fanning, rocking, rotating) can make a big difference in image optimization. Attempt one at a time.

Your patient can often help you acquire better images. If you need them to alter their position or adjust their breathing to help, just ask. Most patients are willing to aid in their own work up if able.

Know your limitations (your own skillset, patient factors, POCUS in general)

Take Home points

While rare, left atrial aneurysms can be seen in both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients, and can be accurately diagnosed with ultrasound

Assessing for LAAs may not one of the key clinical questions for cardiac POCUS but it can be diagnostically helpful when identified, especially because they can lead to life-threatening complications if not treated

Focused cardiac ultrasound can be very useful in the work up and management of numerous presentations in the ED. Have a low threshold to ultrasound any patient, including younger patients, presenting with signs/symptoms that could be cardiac in nature.

Understand probe orientation, develop a systematic approach to cardiac ultrasound, and remember to “follow the clock” to help remember probe orientation and cardiac anatomy

Repetition is key! The more you scan, the better your images, troubleshooting abilities, and diagnostic skills will be. The more normal echos you see, and the more you’ll recognize abnormal!

POST BY: DR. AURYANA DECHICK (R1)

FACULTY CO-AUTHOR/EDITOR: LAUREN MCCAFFERTY, MD

References

Park JS, Lee DH, Han SS, Kim MJ, Shin DG, Kim YJ, Shim BS. Incidentally found, growing congenital aneurysm of the left atrium. J Korean Med Sci. 2003;18(2):262-6.

Morales JM, Patel SG, Jackson JH, Duff JA, Simpson JW, Left atrial aneurysm. Ann Thorac Surg,. 2001; 71(2):719-722.

Cai Y, Wei X, Tang H, Dian K. Congenital aneurysm of the left atrial wall. J Card Surg. 2016;31(12):730-734.

Yetkin E, Atalay H, Ileri M. Atrial septal aneurysm: Prevalence and covariates in adults. Int J Cardiol. 2016;223:656-659.

Yeung DF, Miu W, Turaga M, Tsang MYC, Tsang TSM, Jue J, et al. Incidentally Discovered Left Atrial Appendage Aneurysm Managed Conservatively. Heart Lung Circ. 2020; 29(5): e53-e55.

Wang B, Li H, Zhang L, He L, Zhang J, Liu C, et al.. Congenital left atrial appendage aneurysm: A rare case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(2):e9344.

Herbst MK, Velasquez J, Adnan G, O’Rourke MC. Cardiac Ultrasound. [Updated 2021 Nov 23]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan

Hall KM, Coffey EC, Herbst M, Liu R., Pare JR, Taylor AR., et al. The “5Es” of Emergency Physician-performed Focused Cardiac Ultrasound: A Protocol for Rapid Identification of Effusion, Ejection, Equality, Exit, and Entrance. Acad Emerg Med. 2015 May;22(5):583-93.

Reardon RF, Laudenbach A, Joing SA (2014). Cardiac. In OJ Ma, JR Mateer, RF Reardon, SA Joing (eds), Ma and Mateer’s Emergency Ultrasound (3rd ed). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education. pp 93-167.